We all need to escape every now and then.

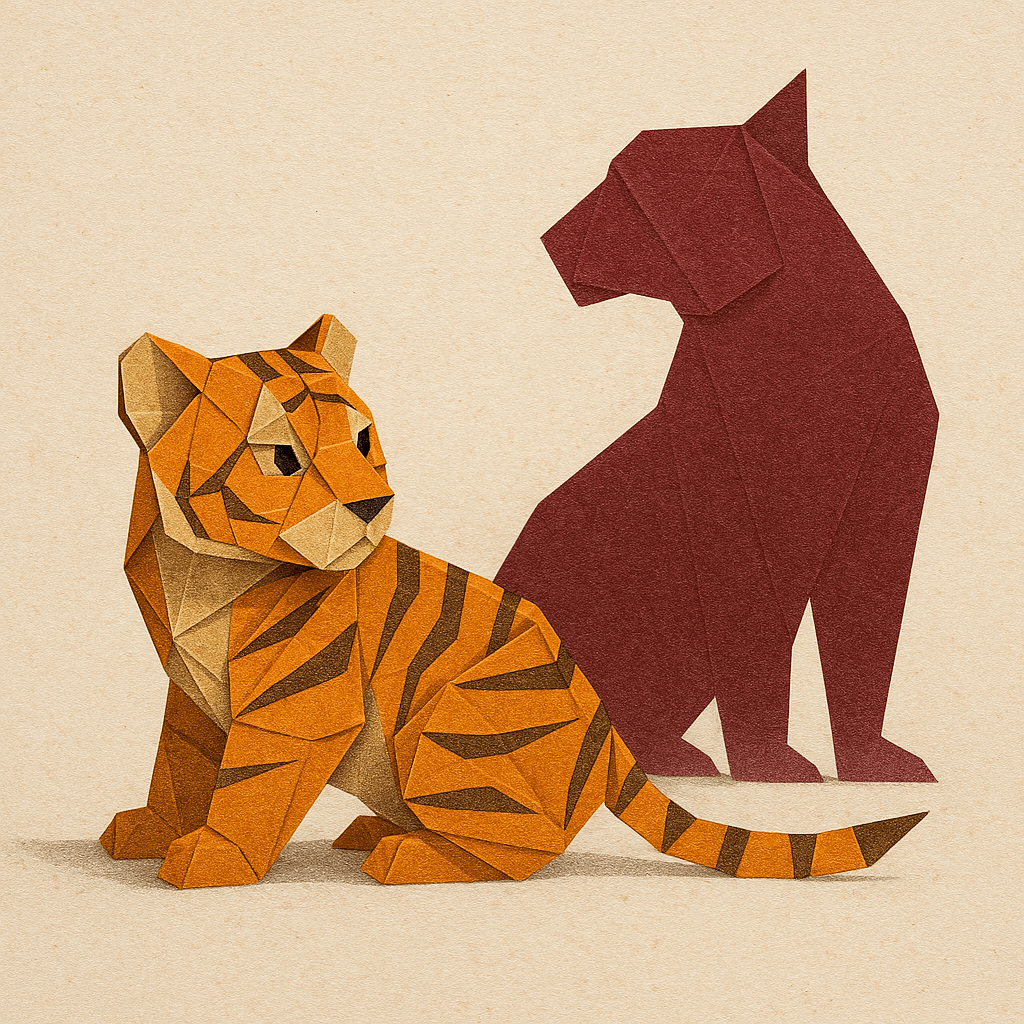

Running into Shadows

Chapter 144: Running into Shadows

In times of hardship, fiction often becomes the most powerful tool we have. Stories and escapist fantasies can trick our minds into forgetting our troubles, even if just for a while. The real world is often too overwhelming to stay grounded in without taking occasional mental detours. Some of us escape to keep from going mad. Others do it for fun. Either way, we all do it. Everyone dreams. Everyone daydreams. This has been true forever—but something feels different now.

In the real world of 2025, technology is so omnipresent that simply being in reality has become difficult. The digital world draws us in with ease. Screens are everywhere, and millions of stories unfold simultaneously—available on demand. Reality and digital fantasy are starting to blur, and people are beginning to notice.

Some embrace this merging of worlds. Others reject it. Some choose to live in the fantasy; others stay grounded in the real. But there’s a danger in fantasy that we rarely acknowledge: stories are sometimes just that—stories. Fictitious and idealized. Not real life.

In real life, there are no guaranteed heroes or satisfying conclusions. The world is often unfair, filled with prejudice, injustice, and cruelty. Fantasy is comforting because it reflects what we wish the world could be. But if we keep pretending our world is ideal when it isn’t, we miss the chance to actually change it.

Now, all of this may sound like I am on the side that rejects fantasy but that’s not the case at all. During the clean up of my mom’s mess, I was in a time of hardship and the pull of fantasy was strong. I’ve never wanted to believe in fiction more than when I found out about my mom’s financial situation. Reality became unbearably painful. I wanted to run away. Desperately. But I couldn’t.

When everything collapsed, fantasy vanished from my mind. I couldn’t consume any media anymore. Sure, there are TV shows about loss and death—but those are on a screen, far removed from the raw, personal reality of financial hardship. When a crisis hits so close to home, you can’t look away. You can’t escape. Reality wraps around you like a vice and refuses to let go.

My cynicism and the anxiety born from financial strain left me unable to suspend disbelief. Movies and shows stopped being enjoyable. I just couldn’t engage with them.

If I had to explain why, I’d say it’s because I needed more realism in the stories I consumed—but my definition of “realism” kept shifting. Nothing felt grounded enough. No story captured what I was going through in a way that could hold my attention. There wasn’t a narrative out there that truly reflected my experience.

So if fantasy failed me, why not turn to something else? Why not look closer?

Yes, I wanted to escape my reality—but that didn’t mean I couldn’t explore the realities of others. And wow. In the world of the internet and social media, you don’t have to look far.

News articles about scammers were everywhere. And with the rise of artificial intelligence, scammers now have some of the best tools on the market. Technology is cheaper than ever. More importantly—and more tragically—the older generation, people like my mom, are falling behind. Tech is evolving too quickly for them to keep up, and they are horrifically underprepared for this new digital age. Our parents are no longer our protectors. We are theirs now. And that transition has been messy—disastrously so.

Full disclosure: I was looking for a little schadenfreude. I wanted to see people worse off than me, just to ease the emotional weight of what I was going through. I was trying to gain perspective. Did it work?

Well… not really.

No matter how much devastation I scrolled through, no matter how much doom I pumped into my phone, none of it helped. It didn’t lift the heaviness already inside me. I had become desensitized to other people’s misfortune—probably because the media just wouldn’t stop with the endless, crushing headlines. And when I needed empathy to help relieve my own burden, it just wasn’t there. I couldn’t feel anything.

I started small—reading stories of others being scammed. There were plenty. Some had it worse than my mom, but not many. And honestly, I think the more someone loses, the less likely they are to talk about it. Shame scales linearly with loss. Looking at national statistics, like those in Canada, didn’t help either. Numbers don’t mean much when you’re in survival mode. When you’ve lost something so personal, it’s impossible to think globally. You’re hyper-focused on what you have left, on keeping it from slipping away.

So, I went bigger.

This was 2023. There was an actual war going on—Russia invading Ukraine. Compared to financial scams, that’s total devastation. In parts of the world, people were losing everything. Sure, we lost money—but how does that compare to a family whose savings evaporated due to hyperinflation? Or to those who lost their homes? Their lives?

How do you even calculate that kind of comparison?

Unfortunately, you don’t. I couldn’t. The scale was too big, too far from my own experience. I just… didn’t care. I couldn’t connect to it. Their suffering wasn’t mine. It didn’t make me feel better. It didn’t make me feel anything.

So, I kept digging. I searched for pain that was more like mine—something I could relate to, but that had even worse outcomes. And finally, I found something.

Well… I unfortunately found something.

I stumbled into Chinese history. It was a subject my mom studied deeply—and it’s also my most direct link to the past. And wow, there were some dark chapters there.

What struck me about this exploration wasn’t just the scale of historical suffering, but how relatable some of it suddenly felt. It gave me perspective—not just on my current situation, but on my mom’s past. For the first time in a while, I could feel something that wasn’t just dread or anger. I could feel context.

My maternal grandma and grandpa were both veterans. They served in the Chinese army—and I think that’s how they met. I remembered this because, fortunately, a bit of that history resurfaced while my grandma was still alive, during a conversation with T1’s Korean wife. When they met, my grandma pulled out her military medals—as well as my grandpa’s—and with T1’s wife translating, they pieced together a startling realization: The grandparents of T1’s wife and mine had once been enemies on the front lines of the Korean War.

How strange fate is—to bring the descendants of former enemies together in a completely unrelated country, far from the battlefield. In a way, it’s kind of wholesome.

There’s more to explore here, but I want to bring this back to the central thread of the story. And yes, I know this might seem like a stretch—but hear me out: the most important part of this story is that my grandma lived through Stalin. Let me explain the influence Stalin’s communist regime may have had on my family.

At first glance, this feels like history with no connection to our present-day crisis. But my mom is a historian—and she grew up just one generation removed from all of this. She not only knew what happened, she had direct access to two people—her parents—who had lived through it. She absorbed that history intimately. All of this to say: yes, my mom has always been political. Even when she was young.

The West—especially after the advent of Christianity and the nuclear family ideal post-WWII—placed a strong emphasis on the individual family unit. In the U.S. and other Western nations, the family is often seen as sacred, a top priority. I think that’s important, because it directly contrasts with one of the biggest stereotypes about Asians: that we’re all about family.

Yes, many of us live in multigenerational households. But that doesn’t always mean there’s a deep emotional focus on the feeling of family. I don’t want to say it’s all a façade—but honestly, sometimes it is. A façade. Hell, I’d even go so far as to say this might be why some Asian parents don’t show sympathy to their kids when they struggle in school. Sure, there’s the perspective that studying doesn’t compare to living through a famine—but maybe, just maybe, there’s also something deeper at play: maybe some Asian parents simply don’t place much emotional value on the wellbeing of their children. Maybe the family unit was never close enough to make that kind of care a priority.

In Maoist China, influenced by Stalinist ideology, the government pushed for loyalty to the state above all else. This indirectly weakened family bonds. My mom likely believed—strongly—that during the Mao era, loyalty to the Communist Party was being engineered through propaganda and subtle forms of brainwashing. Whether or not that’s directly provable, my mom certainly believed it.

And here’s where things get personal.

Let’s say you know this history—about family loyalty being systemically fractured. Would it change the way you view your own family? Should it?

I asked myself this: How did my mom, growing up under the shadow of that history and through the stories of her parents, interpret the meaning of family? Add to that her toxic relationship with my dad—and what do you get?

In my view, a person with a very low sense of family.

Is that really news? Remember her hierarchy of needs? I was never at the top. Neither was “family.” But now, there’s context. Generational trauma, political ideology, and broken relationships show how fragile family bonds can become—and how, when broken, they leave someone disillusioned with the very idea of what a family should be.

It even makes sense, in hindsight, why my mom never liked Disney movies. Those stories about families overcoming anything together? They just didn’t resonate with her.

And maybe—just maybe—this lack of trust in family made her more vulnerable. If the scammers tapped into that mistrust, it might explain why she didn’t tell us what was happening. That silence definitely played a part in the financial collapse that followed. I’m not saying it excuses her choices, but the context helps. It fills in some gaps.

This deep dive gave me something to think about—something more than how shitty my current situation was. It made me wonder: Do Asians really have a strong and healthy sense of family? Are some cultural stereotypes simply manufactured or outdated?

That’s when I decided to dig deeper.

To be honest, I really just needed the distraction.

Subscribe

Sign up to hear updates

Leave a comment