All Asians Look Alike.

Kamikaze

Chapter 145: Kamikaze

So, not all Asians are Chinese, but all Chinese people are considered Asian. That said, we make up a huge portion of the population. China is the most populous—and currently, the most economically powerful—nation in the East.

Why is this important? Well… in the last chapter, I touched on political history. Unlike China, countries like Japan or Korea don’t share a legacy of communist governance. There are ideological and political differences among Asian cultures. What I want to make clear here is that I’m speaking specifically as a Chinese Tiger Cub—not as another type of Asian.

I think this distinction matters because, I’ll admit, as someone who grew up in Canada and has lived there my whole life, I often can’t tell the difference between different Asian ethnicities. In a multicultural country like Canada, where English and French are dominant, language cues don’t help much either. Honestly, we do tend to look alike. The stereotype has a bit of truth to it.

Speaking as an Asian person, I don’t really dwell on these differences. Race will always be a part of the equation, but I prefer to believe that character and actions define me more than ethnicity. I mentioned before my belief in an internal locus of control, so it shouldn’t be surprising that I’m not a big fan of affirmative action. I like to think that merit earns recognition—not factors beyond your control. But let me be clear: that doesn’t mean I “don’t see color.” I do. I think it’s necessary to acknowledge it. Biology has hardwired us to see both similarities and differences in others, and ignoring that reality is, in my view, shortsighted.

Have you read The Selfish Gene? It’s a great read, especially for those of us who grew up immersed in STEM. The premise is simple: our genes are the driving force behind much of what we do. Genes have one primary goal—survival through propagation. This evolutionary imperative explains not only parent-offspring relationships but also certain types of altruism.

Here’s how it works in a family setting: If I have children, they carry my genes to the next generation. They’re my shot at continuing the line, so I’m naturally inclined to protect them—even at the cost of my own life.

Now take that same logic and apply it to strangers: If I’m part of a group of unrelated people and I’m older, I might instinctively gravitate toward someone who looks like me. Why? Because they might share more of my genetic traits than someone who looks very different. That unconscious recognition may compel me to protect them—again, even at my own expense. We are, in this view, operating in service of our genes.

This brings us to an important implication: we tend to have a slight affinity toward people who look like us. I want to emphasize that this is just one interpretation of The Selfish Gene—and arguably not the strongest one—but it’s useful for this discussion.

So, the idea is that we’re drawn to people who resemble us. We see this in society too. TV shows and movies often feature main characters who mirror the target audience’s identity. It’s easier to empathize when the protagonist looks or feels familiar.

Now take that instinct—the preference for those who look like you—and put it in a multicultural society. What do you get? Tribalism. Or at least a version of it. We instinctively side with people who resemble us more than those who don’t. In a world filled with visual diversity, we tend to gravitate toward those who reflect our own appearance. We project onto them. We try to help them more.

But what happens when you’re surrounded by people who all look like you? What does that instinct do in a sea of similar faces—like growing up among other Asians who genuinely do resemble one another?

Our story exists mostly within the world of my mom, who didn’t grow up in Canada or a multicultural society. She was raised in a homogenous China. A place where everyone looks the same. Also, as we discussed in the last chapter, you carry the psychological remnants—or at least some ideological influence—from a political system that demanded loyalty to the state over loyalty to family. Where do you go from there?

I see two possible mental paths that might emerge from such a background. For the sake of structure, I’ll focus on the first scenario in this chapter:

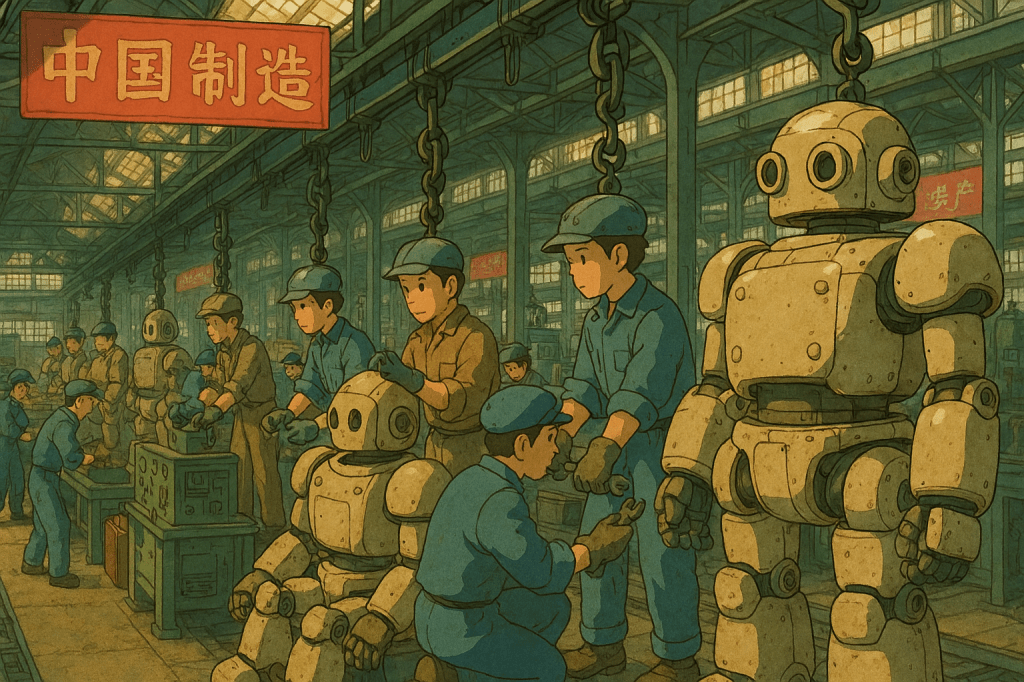

All Asians Look Alike

Let’s suppose that growing up surrounded by people who all looked like you made you think: We must all be the same. From a Western perspective, this might sound dystopian. No individualism? No self-expression? A terrifying thought. But here’s the twist—if you come from a family like mine, where parental bonds were weak or distant, the idea of being part of a collective might be comforting. If home doesn’t give you belonging, society can. You may not feel loved by your family, but at least you belong somewhere.

In this context, I imagine two psychological outcomes:

1. The Superman Scenario

In this version, you embrace the idea that everyone is the same and feel deeply connected to others. You believe that if everyone is like you, then helping others means helping yourself. You work toward the collective good with selfless dedication. You imagine a better society, and you feel both responsible and capable enough to help build it. This is idealism through collectivism—the dream the Communist Party of China once sold. The challenge, of course, is that it depends on two things:

- A genuine desire to uplift the community.

- A belief that you have the ability (and freedom) to make a difference.

2. The Stalin Scenario

Here’s the darker path: If everyone is like you, and you know your own flaws, then everyone else must share those flaws too. You begin to believe that unchecked behavior must be controlled, because left to our own devices, we’d all fall into chaos. In this view, collectivism is about surveillance, not support. It’s about keeping each other in line to preserve stability. While I’m using “Stalin” symbolically, the reality is that this approach echoes real historical regimes—ones that thrived on conformity and control.

Yes, I know I said I wouldn’t get political and now I’m name-dropping Stalin. That contradiction isn’t lost on me. But to be fair, I’m diving into the shadows of the old world, not today’s politics. I’m not critiquing current governments—I’m exploring historical context that helps explain how my family thinks.

And that brings us back to my family.

In both the Superman and Stalin scenarios, the individual is secondary. You matter only as a part of something bigger. You’re only valued when you serve a purpose: either to support the collective or to maintain its order. The “greater good” always overrides personal freedom.

Now, to be clear—my mom isn’t a supporter of the Stalinist mindset, nor is she loyal to the CCP. She left China for a reason. But consciously or not, she still absorbed the idea that the individual doesn’t matter unless they serve a greater cause. That thinking didn’t disappear just because she crossed an ocean.

When taken to the extreme, this worldview creates a stark contrast between East and West. In the West, individuals are seen as irreplaceable; in the East, they’re often seen as replaceable. Western societies are built around “No one gets left behind.” Eastern cultures lean toward “Sacrifice yourself for the whole.” In the West, the individual is often celebrated. In the East, the group is usually prioritized.

You can even see this in religious traditions. The West, influenced by Christianity, emphasizes loving your neighbor and the value of each soul. The East, shaped by Confucianism, Buddhism, and collectivist philosophies, tends to focus on harmony, duty, and social order.

Remember how I said my mom has a strong sense of righteousness? That she always feels the need to do what’s “right”? I think that stems from this cultural framework. I call it ego—but she probably calls it duty. She believes it’s her role, her responsibility, even her calling, to act for the greater good. Her pride in doing what she believes is right doesn’t come from personal ambition—it comes from a deep, internalized belief in service. Whether that belief is misguided or not, it has context. And that context is what I’m trying to understand.

Now here’s the uncomfortable truth about the Stalin Scenario: if your job is to keep others in line—and someone steps out of line—you don’t try to understand them. You punish them.

Because, if everyone is equal and the same, there’s no room for excuses. If someone stumbles, it must be because they chose to. And when the individual doesn’t matter, their suffering doesn’t either.

That’s the worldview my mom carried. That’s the generation she came from. And it’s part of the reason why, when things went wrong, we blamed her.

Not the scammer.

Not the system.

Her.

I get that it sounds harsh. It is harsh. But when I look at how I was raised, it makes a certain brutal kind of sense. I was taught to believe in a greater good—but my version of that good was the family. And when my mom let a criminal tear that apart, it felt like betrayal, not victimhood.

Now, if you’ve read earlier chapters, you’ve already seen this dynamic play out in my childhood. But this story isn’t about kids. It’s about how we don’t forgive adults. It’s about what happens when someone who’s supposed to be strong… fails.

So let me tell you one last story. It’s about my dead uncle.

He was my dad’s brother. He helped my dad pressure my grandma and uncle into handing over my inheritance—nine out of ten insurance policies set up for me at birth. My dad ran off with that money, started a new family in New Zealand. And my uncle? I assume he used his share to fund the drug binge that killed him.

And yes, I know. Speaking ill of the dead, even the messed-up ones, is taboo. But I was raised not to care about that. My paternal grandparents didn’t. When my uncle died, they had nothing kind to say—not even at his funeral.

In some corners of Asian culture, if you fall behind, you’re disposable. If everyone starts from the same place, failure means there’s something wrong with you.

Not the world.

Not the system.

Just you.

And if people can’t muster sympathy for someone who dies that way, imagine how little they have for the living. That’s the kind of silence I grew up in. No excuses. No grace. Just results.

When I failed at school in Canada, my mom didn’t care that I didn’t speak English yet. She didn’t ask why. She only saw that I was losing—and in her world, losing meant weakness. Weakness meant shame. And shame meant you were no longer worthy of protection.

So when she messed up, I treated her the same way. No sympathy. No context. Just judgment.

When you’re taught that everyone is just like you…you stop asking what happened to them—and start asking what’s wrong with them.

You stop seeing struggle. You only see failure.

And in a world where failure is weakness, and weakness is shame…Sympathy dies.

And all that’s left is apathy.

Subscribe

Sign up to hear updates

Leave a comment