Asians Don’t All Look Alike.

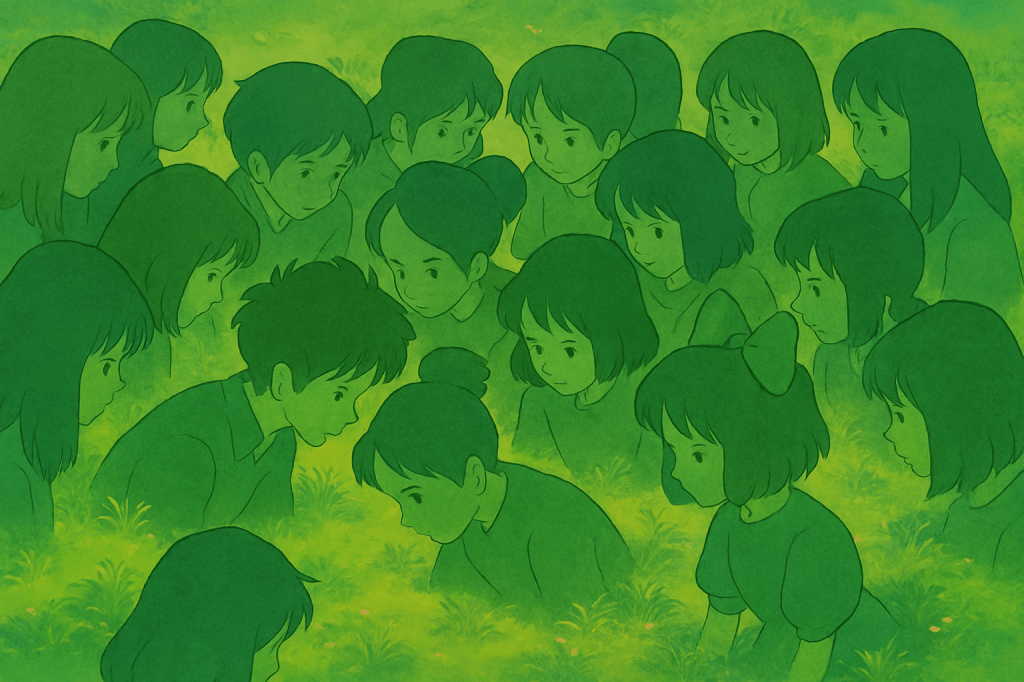

Shades of Green

Chapter 146: Shades of Green

During the preparation for the Moldova humanitarian mission trip, one of the organizers—a middle-aged Caucasian man—sat down with everyone attending to talk about what to expect. He was fairly organized and full of information about how these trips typically ran. I appreciated that you could really hear the experience in his voice. It made what he said feel weightier—and, to be frank, his PowerPoint was kind of bare, so his delivery had to do the heavy lifting.

The most important parts of his talk were about lodging and the food we could expect. As he was describing the meals, he looked at a particular group in the room—the cluster of Asian students—and said:

“Oh, and don’t worry, they serve rice in Moldova. I checked.”

My exact reaction at the time? I found it hilarious. Some of my lighter-skinned classmates, however, did not.

For context: our optometry class of 90 students was over 60% female and more than half Caucasian. During a break from the info session, some of those Caucasian classmates went up to the speaker and confronted him about the remark, which they found inappropriate.

Then those same classmates came to me and told me not to worry. I was kind of touched. One of them—bless her heart—stood up for me. She told me that what the presenter said had been noted, and that it was unacceptable. She’d make sure it didn’t happen again.

I turned to her and asked—half-jokingly—“Okay, but we are getting rice in Moldova, right?” She chuckled awkwardly.

I felt the need to explain myself after that, because I could tell the situation was starting to spiral. I think most of the Asian classmates who were asked about the comment said the same thing: we weren’t really offended. It was just a joke. Honestly, that’s all it was. Later, it just became a funny story to tell.

Jokes like these don’t really happen in a homogenous society. When everyone looks the same, there’s no room for jokes about preferences, cultures, or practices. Sure, this story is light-hearted and nothing truly offensive was said—but the truth is: these are the only types of stereotypes I’ve really encountered. I’ve never experienced a hostile racial moment.

Now, you might think that’s because I started off in the homogenous society of China—but that’s not what I mean. I’m talking about Canada. Even here, I never really felt that level of racism. Or at least, not from other races. Any discrimination I felt—if you can even call it that—usually came from people who looked like me.

Remember in high school when I got ostracized in the Chinese orchestra? Remember how mild that entire experience was and how it really didn’t amount to much at all? Yeah. That was the only type of discrimination I faced. It wasn’t much.

Most of that was probably because I didn’t have a parent who could suck up to the higher-ups. And of course, there were the very obvious themes of merit and actual music ability. But if you nitpick, you could say I was discriminated against because I didn’t have the luxury of a parent who could take time off to cater to the orchestra’s needs.

Not a very strong case of discrimination—but here’s the thing: the narrative still works. It’s still easy to see.

When my mom found out about all of this years later, her reaction was that Chinese people were always so eager to discriminate based on money. Whether she was right or wrong didn’t really matter. Her immediate leap to a money-based explanation says a lot.

What I got out of all this was that, while you might think racism wouldn’t exist if everyone looked like you—that’s just not true. Or at least, it wasn’t true in my mom’s experience. When a society is that uniform—like the China she grew up in, or the Chinese-Canadian community I grew up in—we don’t stop needing to belong to a tribe. We just find new ways to divide. We nitpick.

And that’s why the stereotype that “Asians all look alike” is so wrong.

Asians Don’t All Look Alike.

We all have different shades of green. And that’s enough for us to draw lines between who’s “us” and who’s “them.”

In my mom’s world, wealth was the dividing line. Growing up, whenever my family wanted to build relationships or boost our social standing, we gave expensive gifts. The more costly, the better. Forget the thought behind the gift—everything was a power play.

In a community where that’s the norm, it becomes nearly impossible to separate money from identity. Money lets you give better gifts. It lets you show class. You need it for everything—and for everyone.

We worshiped money. And that’s not even hyperbole—there are literal gods of money in Asia.

This obsession comes from the prestige and status that wealth brings. Even if you ignore my high school chapters and the music stories, you’ll still see how often money comes up. That’s because my mom was counting every penny throughout my childhood. She came from a society that placed immense value on wealth. And since we were poor when we arrived in Canada, that drive only grew stronger.

She talked to me about rent, food, cello lessons, tutor fees—everything—as a way to motivate me. For her, it was about survival and progress. For me, everything I did was tied to one goal: get a job and make money.

As an adult, that sounds normal. But when that’s your reality as a kid—is that really necessary? That’s something you have to decide for yourself.

As I’ve said before, I’m the product of a success story born from the Tiger Parent model. It works. Hardships aside, it’s one way to bring out someone’s potential. It’s not for everyone—but it works for some. But that’s not the full story here, is it?

For my mom, the tools of her Tiger Parenting were rooted in her own personal hierarchy of values: pride and money. Both of which she lost with the scam. So now, here’s the question I’m left with: If a society places everything on material wealth and generational status— How do you lose that?

How deep in the hole do you have to be to give up the one resource that opens every door in your value system? How do you get tricked out of that? Asians don’t all look alike—we discriminate with money. And when that’s the system, and wealth sits so high in the value hierarchy, how do you not defend it better?

How do you not hold it close? Keep it in check? Guard it like your life depends on it? For all the crap my mom gave me back in the day—for not being good enough at school, at cello, at anything really— why didn’t she check herself for her own inadequacies?

You can tell we’re coming back around now after this deep dive into the world of Stalin and Communism. I’ve gone into the shadows of the old world to see if I can find reason and unfortunately, still can’t get a true perspective or an explanation as to why my mom fell so deep into a hole.

The entire bit was a good escape from the truth but it wouldn’t be forever.

Research can only yield so much context.

Subscribe

Sign up to hear updates

Leave a comment